|

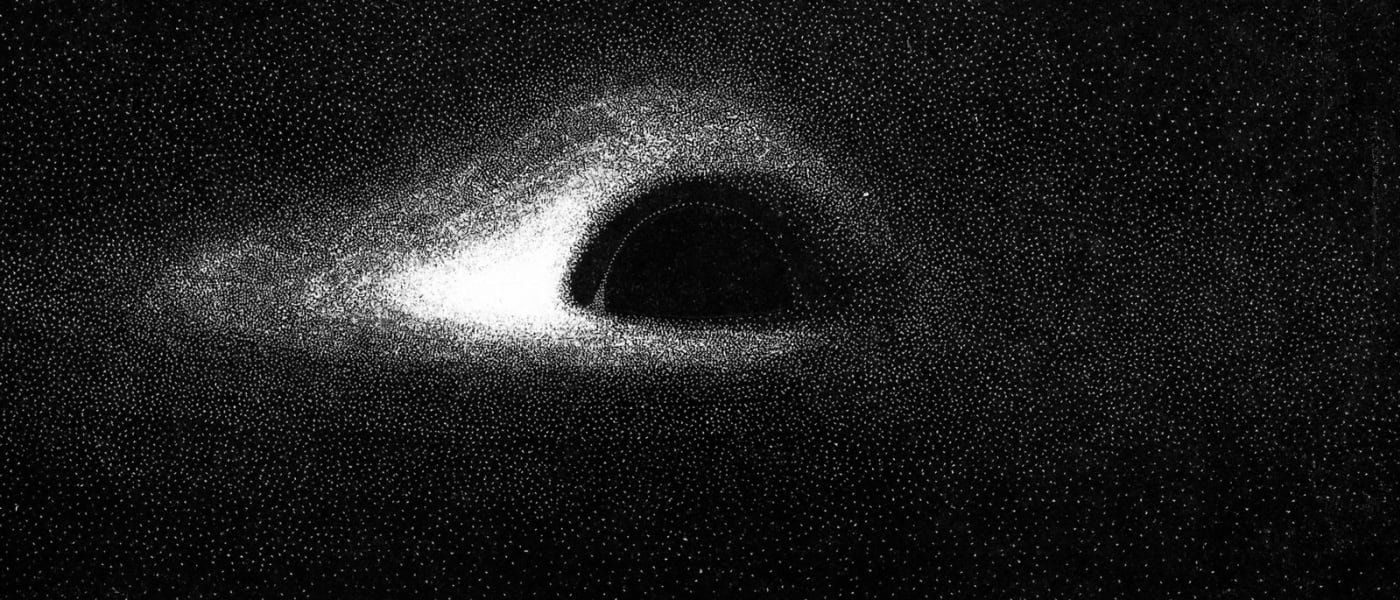

| Image credit: Jean-Pierre Luminet |

Black holes are so

outlandish that the scientists who first thought them up figured they couldn't

possibly exist in reality. They form from massive, collapsed stars and are so

dense that nothing can escape their gravitational pull, including light. Black

holes mess with spacetime so badly that scientists have long wondered: How do

these things look, exactly?

We may be on the cusp of

seeing one thanks to the Event Horizon Telescope, but back in 1979, Jean-Pierre

Luminet created the first "image" using nothing but an early

computer, lots of math and India ink.

The problem with imaging a

black hole is that, by definition, they don't emit light or radiation. Luckily,

large black holes are usually next to other stars and suck away their matter,

something astronomers can see. "As [gases from stars] fall towards the

black hole, it becomes hotter and hotter and begins to emit radiation.

This is a good source of

light: the accretion rings shine and illuminate the central black hole,"

writes Luminet in his e-Luminesciences blog.

The distinguishing feature

of a black hole is its "event horizon" boundary, the point of no

return for matter and light. At its periphery, materials sucked in from

adjacent stars form an "accretion disk," famously depicted in

Interstellar (below) as two bright, perpendicular disks.

That's just an illusion,

though -- there's only one disk at the equator, but the light is bent upward by

the black hole's extreme gravity (via gravitation lensing).

Luminet's stunning image

depicts two other important phenomena not seen in Interstellar movie.

You can read the complete article here.