Believe it or not, according to the Index of Objects Launched into Outer Space maintained by the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs, there were 7,389 individual satellites orbiting our little planet at the end of April 2021 (others place the number closer to 6,500). This number is only set to increase over time, with some estimates coming in at around 990 satellites being added to the mix every single year.

If true, by about 2028, we can expect to see somewhere in the order of 15,000 satellites orbiting Earth. This includes the massive increase in satellites scheduled to be deployed by companies like SpaceX in their Starlink constellation. The rise of small CubeSats, microsats, nanosats, etc, may also increase the number several-fold over the coming decades or so.

Of the satellites in space, most are used for either commercial telecommunications or navigational purposes, with others used for scientific or military purposes.

The vast majority, around 60%, is actually defunct and have been left to their fate.

Often referred to as "space junk", these long-dead satellites, as well as other pieces of metal and equipment are increasingly becoming a potentially serious navigational hazard for current and future spacecraft.

Vanguard 1C, for example, was launched in 1958. The American satellite was the fourth artificial Earth-orbiting satellite to make it to space, launching about five months after the more famous Soviet Sputnik 1.

Powered by solar cells, all contact was lost with Vanguard 1 in 1964. It still orbits the Earth (along with the upper stage of its launch vehicle), and is officially the oldest piece of "space junk".

"Space junk" is also introduced into orbit from the delivery vehicles used to get this stuff into orbit too. This can include small pieces of metal or paint flecks up to larger chunks of hardware like booster rockets, etc.

Why is space junk a problem?

If you've ever seen the film "Gravity", you will probably have, an admittedly dramatized, but basic idea. At present, while there is a lot of stuff up there, space is a big place and current levels of this junk are not mission-critical just yet.

The biggest risks associated with it all are from existing hardware already in orbit. Most modern satellites and other spacecraft have some form of collision avoidance system to help move them, briefly, out of the way of any incoming junk. The International Space Station (ISS) also has a similar system in place and it is used quite frequently.

But, even with all that in place, collisions can and do occur. In March of 2021, for example, a Chinese satellite broke apart after being hit by some space debris. Another similar event occurred in 2009.

But, can anything be done about it? Actually yes.

Various initiatives are currently underway to help clean up the space around Earth. Some strategies involve using existing satellites to grab pieces of space junk, while others focus on deorbiting satellites once they have reached the end of their usefulness, sending them careening into Earth's atmosphere to burn up instead of floating around in space for decades.

Not very sophisticated, perhaps, but it is effective nonetheless.

Examples include Surrey Satellite Technology's RemoveDEBRIS mission which used a large net to capture old satellites. While effective on larger objects, even this kind of system would miss the smaller stuff like paint flecks.

The United Nations has requested that all companies have a policy to de-orbit old space tech after 25 years or so, but this relies on compliance being voluntarily undertaken.

Time will tell if more effective strategies can be developed to manage space junk in the future. But, as you are about to find out, we may not want to clear up space entirely.

Some of these "dead" spacecraft may still function!

1. Voyager 1 and 2 are still going strong

Perhaps the most famous example of old spacecraft still in use today are Voyager 1 and 2. By far the farthest-traveled human-made objects ever sent into space, these amazing pieces of kit are still faithfully sending data back to Earth.

Voyager 1 was launched in September of 1977, with Voyager 2 sent a little earlier, in August of the same year.

The Voyager spacecraft were built at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California and funded by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), which also organized their launches from Cape Canaveral, Florida, their tracking, and everything else concerning the probes.

Designed as interstellar probes, they have more than surpassed expectations over their lifetimes with both now way past the boundary of the heliosphere of our solar system.

Sadly, however, while both are still transmitting data, they are also coming to the end of having enough power to transmit data. Voyager 1 is already using backup thrusters to keep its antenna pointed toward Earth and it is expected that by around 2025, both crafts will finally exhaust the power necessary for them to collect data and transmit it back to Earth and the signals will, finally, stop.

However, for having a mission that will have lasted nearly 50 years (1977–2025), I think they meet our criteria.

2. LES-1 is what is technically known as a "zombie satellite"

Another of the oldest, sort-of functional, artificial objects in space is LES-1. Also known as the Lincoln Experimental Satellite 1, it was originally designed as a communications satellite.

LES-1 was launched into Earth's orbit in February of 1965 from Cape Canaveral, Florida with the specific task of studying the use of ultrahigh-frequencies (UHF) radio transmissions. LES-1 was never able to reach its optimal orbit, due to a wiring error causing the rocket motor to fail to fire as intended, and the satellite shut down its transmitters in 1967.

LES-1 was the first of a series of satellites that formed MIT Lincoln Laboratory's first foray into the building and testing of communications satellites. The main goal of the project was to increase the transmission capabilities of communications satellites that were limited due to their inherently small size.

LES-1 has a roughly polyhedral body shape, is round 5-feet (1.5m) tall, and was powered by a series of solar calls clad to its main body. The satellite was designed to last for about 2 years, during which it would take part in telecom experiments from base stations in Westford, Massachusetts, and Pleasanton, California.

Believed to be a lost cause, LES-1 was largely forgotten about by the world until it spontaneously began to resume radio transmissions in 2012. The signals from LES-1 were first detected by Phil Williams from Cornwall, England, UK, and were later verified by other zombie satellite hunters. Apparently, a short had developed in the satellite’s systems allowing power from the solar cells to reach the transmitter directly.

3. LES-5 is still very much open for business

Hot on the heels of LES-1 is its younger sibling LES-5. Also built by MIT's Lincoln Labs, it was launched into orbit in 1967.

Like other LES satellites, LES-5 was built to test the viability of a satellite-based military communications program and was placed in a geosynchronous orbit. The satellite was used until 1971, after which its mission was deemed complete and it was deactivated.

LES-5 was then sent into what is termed a "graveyard orbital slot" used by many other redundant spacecraft. Since then, LES-5 has effectively been largely forgotten about and ignored.

LES-5 was one of nine other experimental satellites for use as testbeds for a variety of devices and telecom techniques for the United States Air Force. LES-1 was launched in 1965, with the last LES-9, launched in 1976. Most of these are still in orbit, with LES-3 and LES-4 officially destroyed when they entered Earth's atmosphere.

However, in 2020, a self-described dead satellite finder, Scott Tilley, found that the telemetry beacon for LES-5 was still transmitting at 236.75 MHz. Whether or not you consider this as a "working" satellite, or not, it is fascinating to find such early space tech still working.

4. Transit 5B-5 still kind of works

Another technically functional piece of "space junk" is the Transit 5B-5 satellite. It was part of the Transit/Navsat navigational satellite program.

First launched into orbit in 1964, it acted as a telemetry transmitter and can still occasionally transmit at 136.650 MHz when it's passing through sunlight.

At launch, it has a nuclear power source and was carried into space by a Thor Star rocket.

According to NASA, "the Transit spacecraft were developed for updating the inertial navigation systems onboard US Navy Polaris submarines, and later for civilian use. Transit receivers used the known characteristics of the satellite's orbit, measured the Doppler shift of the satellite's radio signal, and thereby calculated the position of the receiver on the earth."

The Transit system was superseded by the Navstar global positioning system. The use of the satellites for navigation was discontinued at the end of 1996 but the satellites continued transmitting and became the Navy Ionospheric Monitoring System (NIMS).

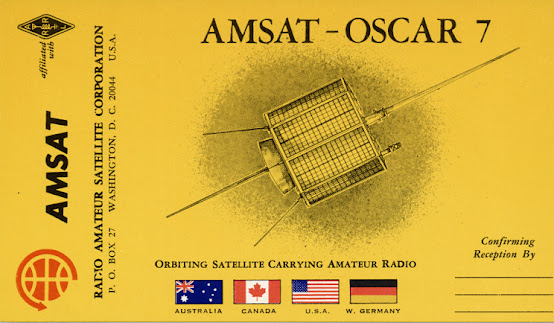

5. AMSAT-OSCAR 7 continues to function just fine

Yet another "zombie satellite" in orbit around planet Earth is AMSAT-OSCAR 7 (AO-7). It was the second so-called "Phase 2" satellite designed and built by the Radio Amateur Satellite Corporation, or AMSAT for short.

Launched into orbit in November of 1974, the satellite worked as expected for many years until its batteries finally died in mid-1981.

AO-7 carries two amateur radio transponders. The first, its "Mode A" transponder, has an uplink on the 2-meter band and a downlink on the 10-meter band. The second called its "Mode B" transponder, has an uplink on the 70-centimeter band and a downlink on the 2-meter band.

AO-7 also carries four beacons which are designed to operate on the 10-meter, 2-meter, 70-centimeter, and 13-centimeter bands. The 13-cm beacon was never activated due to a change in international treaties.

The satellite has also played its part in global affairs too. In the summer of 1982, the anti-communist Polish Solidarity movement learned that AO-7 was periodically functional when its solar panels got enough sunlight to power up the satellite. Activists used the satellite to communicate with Solidarity activists in other Polish cities and to send messages to the West. Since the regular telephone network was tapped by the government and ham radios were easy to track, the satellite link was an invaluable asset.

Miraculously, after several decades of silence, the satellite began to resume transmissions in June of 2002. The reason appears to be the fact that one of its batteries shorted, allowing it to become an open circuit and allow the spacecraft to run off its solar panels when the satellite is in direct sunlight.

Today, AO-7 is officially one of the oldest remaining communications satellites in existence.

6. Prospero might still be functioning too

Another old piece of kit in space that might just work is the British-made satellite called Prospero, also known as the X-3. The satellite was launched from Australia in 1971 - the first and only UK spacecraft to be launched on a British-built rocket, the Black Arrow.

Built by the Royal Aircraft Establishment in Farnborough, England, the satellite was originally going to be called "Puck". The satellite weighs around 146 pounds (66kg) and currently occupies a low-Earth orbit.

The satellite was designed and built to act as a platform for a series of experiments to study the effects of space on communications satellites. Prospero remained operational until around 1973, after which it was in contact every year for the next two and half decades.

Prospero's tape recorders stopped working in about 1973, and the satellite was officially decommissioned in 1996, although its signals were still detectable. At present, it is expected that the satellite's orbit will decay in about 2070.

Plans are afoot by British company Skyrora and collaborators to attempt to capture and retrieve the satellite for posterity in a museum.

7. Calsphere 1 and 2 are both still going strong

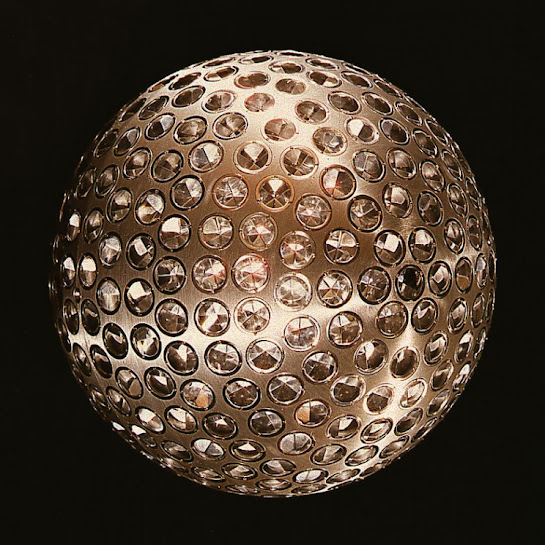

Perhaps the oldest, still functional, spacecraft are Calsphere 1 and 2. Launched in 1964, both Calspheres were delivered into space using the same Thor Able Star rocket from Vandenberg Air Force Base.

Designed as U.S. Navy electronic intelligence satellites, each weighs just under a kilogram and is roughly spherical in shape. They are what is termed a passive surveillance calibration target, and they were both built by the Naval Research Laboratory.

Since both lack an independent power supply of any kind, and are basically large metal spheres, they are technically still "operational". However, we'll let you decide if they would actually count as true spacecraft or not.

Other large metal spheres which were launched shortly after Calspheres 1 and 2 are also still in orbit. These include, but are not limited to, Tempsat-1 (launched in 1965), Lincoln Calibration Sphere 1 (LCS-1, also launched in 1965) to name but a few.

8. LAGEOS-1 is aging, but still works

Yet another old piece of tech in space that still kind of works is the Laser Geometric Environmental Observation Survey 1, LAGEOS-1 for short.

Designed and launched by NASA in 1976, it is one of a pair of scientific research satellites. LAGEOS-1 is still in use to this day.

LAGEOS was designed to provide laser-ranging tasks for geodynamic studies on Earth, and each of the LAGEOS twins carries a passive laser reflector. LAGEOS is a passive satellite and has no power, communications, or moving parts. Satellite "operations" consist of simply the generation of the orbit predictions necessary for the stations to acquire and track the satellite. Both LAGEOS-1 and 2 both currently hold a medium Earth orbit.

LAGEOS-1 was used by transmitting pulsed laser beams from the Earthbound ground station to the satellites. The laser beams would then return to Earth after hitting the reflecting surfaces. The travel times would then be precisely measured, permitting ground stations in different parts of the Earth to measure their separations to better than one inch in thousands of miles.

They both consist of a 24-inch (60 cm) aluminum-covered brass sphere that weighs between 882 pounds (400 kg) and 906 pounds (411 kg) for LAGEOS-1 and 2 respectively.

Amazingly, LAGEOS-1 has another "secret" mission once its current activities are complete. The satellite contains a small plaque designed by Carl Sagan that is intended to act as a kind of time capsule for future generations.

On it is a series of information including binary code, as well as diagrams showing how Earth's continents appear in the past, today, and 8.4 million years in the future, the estimated lifetime of the LAGEOS spacecraft.

9. ISEE-3 is still orbiting the Sun waiting to be reactivated

And finally, the International Sun-Earth Explorer 3 (ISEE-3). Launched in 1978, it was the first spacecraft to be placed in a halo orbit at the L1 Earth-Sun Lagrange point.

ISEE-3 is one of three spacecraft along with the "mother-daughter" pair of ISEE-1 and 2. Later renamed ICE-3, this satellite/probe became the first spacecraft to visit a comet when it passed through the plasma tail of the comet Giacobini-Zinner in 1985.

NASA suspended routine contact with ISEE-3 in 1997 and made brief status checks in 1999 and 2008. Since then, two-way communication was reestablished with the probe in 2014, with support from the Skycorp company and SpaceRef Interactive.

The team was even able to fire up the probe's thrusters briefly, but further attempts failed due to an apparent lack of nitrogen pressurant in the fuel tanks. Further attempts were made to use the probe to collect other data, but as of September 2014, all contact has since been lost.

And that, clapped-out spacecraft fans. is your lot for today. These are but a few of the thousands upon thousands of functional, zombie, and passive pieces of technology our species has sent rocketing into orbit or off to distant stars and planets.

While most are still crowded around our planet like some kind of debris haze, others have traveled so far away from us that we are unlikely to never, ever, see them again.