A G1-class geomagnetic storm hit the Earth last Saturday, causing bright auroras over Canada, Newsweek reported. The only problem is that nobody saw this storm coming until it was quite late.

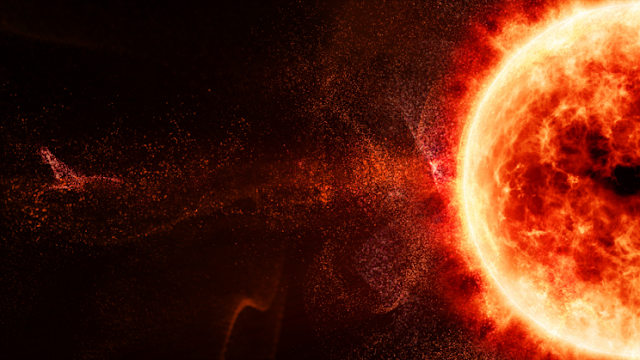

Solar scientists have been watching the skies with anticipation of solar activity after a sunspot grew enormously earlier last week, and then a huge coronal mass ejection (CME) was spotted on the solar surface. A big solar storm was expected due to the latter, but scientists were not very sure if it was heading towards the Earth.

After a long two-day wait, no worrisome geomagnetic activity was noticed, and solar scientists may have breathed a sigh of relief. But the recent report showed that even after watching the solar surface so closely, our Sun is full of surprises and, from time to time, throws us a curve ball.

How bad was the geomagnetic storm?

According to the Newsweek report, the geomagnetic storm was predicted by the Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC) of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration on the evening of June 25. The space weather prediction agency also said that the storm would last through the night and into the morning.

The SWPC predicted the geomagnetic storm to be of G1-class, the lowest classification in terms of power and impact of the storm. A G5-class is the highest classification of a geomagnetic storm that we have so far.

A G1-class geomagnetic storm carries risks such as an impact on satellite operations and power grid fluctuations. However, due to the relatively weaker intensity of the storm, the impact of the risks is also lower. Energy transfers during such events also produce some beautiful auroras that are visible in the night sky, and astronomers told Newsweek that they observed auroras in Calgary, Alberta.

What caused the geomagnetic storm?

Even as the geomagnetic storm made little difference other than the shimmering natural lights, it also set astronomers looking through their data for what could possibly explain how they missed spotting such an event earlier.

At first, the scientists were looking for occurrences of CMEs that may have gone unnoticed. However, further analyses showed that the geomagnetic storm was caused by a rare and harder-to-spot phenomenon called the co-rotating interaction region (CIR) of the Sun.

According to Spaceweather.com, a CIR is a transition zone between the slow and fast-moving streams of solar wind. These zones can also cause build-ups of plasma which have intensities of a CME, but they are not accompanied by the formation of a sunspot. Since space weather predictions largely look at sunspots, this geomagnetic storm was missed until late and hit the Earth at 1.57 million miles (2.52 million km) per hour. This is more or less in the region of how CIRs hit, Live Science said in its report.

The incident reinforces the need to keep looking at our Sun using a variety of techniques, especially when it is going through an active phase of its solar cycle, as a Carrington-like event could be really devastating today.

Reference(s): Newsweek