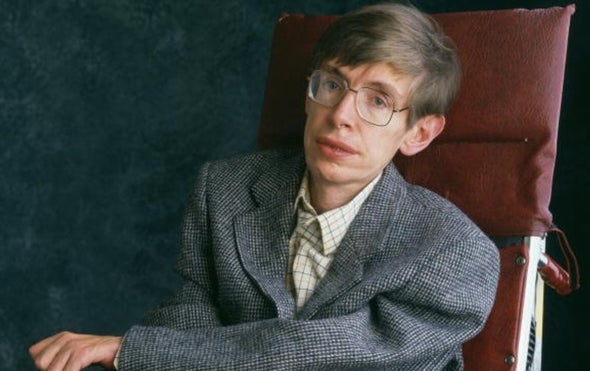

Groundbreaking physicist

Stephen Hawking left us one last shimmering piece of brilliance before he died:

his final paper, detailing his last theory on the origin of the Universe,

co-authored with Thomas Hertog from KU Leuven. The paper, published today in

the Journal of High Energy Physics, puts forward that the Universe is far less

complex than current multiverse theories suggest.

It's based around a concept

called eternal inflation, first introduced in 1979 and published in 1981. After

the Big Bang, the Universe experienced a period of exponential inflation. Then

it slowed down, and the energy converted into matter and radiation.

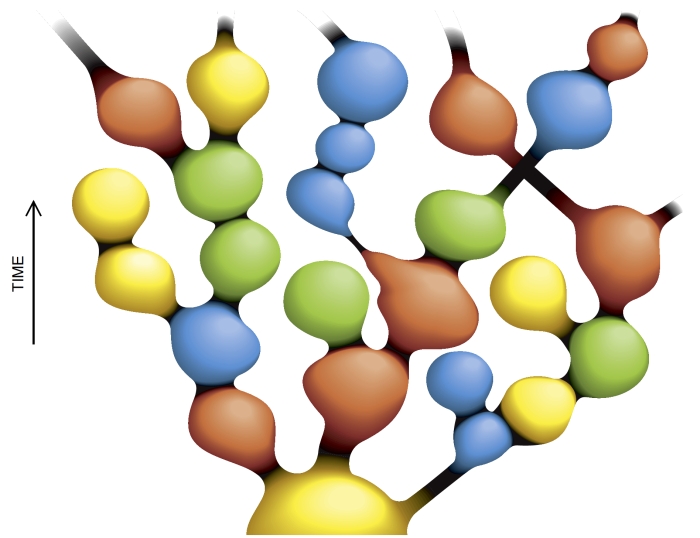

However, according to the

theory of eternal inflation, some bubbles of space stopped inflating or slowed

on a stopping trajectory, creating a small fractal dead-end of static space. Meanwhile,

in other bubbles of space, because of quantum effects, inflation never stops -

leading to an infinite number of multiverses. Everything we see in our

observable Universe, according to this theory, is contained in just one of

these bubbles - in which inflation has stopped, allowing for the formation of

stars and galaxies.

"The usual theory of

eternal inflation predicts that globally our universe is like an infinite

fractal, with a mosaic of different pocket universes, separated by an inflating

ocean," Hawking explained.

"The local laws of

physics and chemistry can differ from one pocket universe to another, which

together would form a multiverse. But I have never been a fan of the

multiverse. If the scale of different universes in the multiverse is large or

infinite the theory can't be tested."

Even one of the original

architects of the eternal inflation model has disavowed it in recent years. Paul

Steinhardt, physicist at Princeton University, has gone on record saying that

the theory took the problem it was meant to solve - to make the Universe, well,

universally consistent with our observations - and just shifted it onto a new

model.

Hawking and Hertog are now

saying that the eternal inflation model is wrong. This is because Einstein's

theory of general relativity breaks down on quantum scales.

"The problem with the

usual account of eternal inflation is that it assumes an existing background

universe that evolves according to Einstein's theory of general relativity and

treats the quantum effects as small fluctuations around this," Hertog

explained.

"However, the dynamics

of eternal inflation wipes out the separation between classical and quantum

physics. As a consequence, Einstein's theory breaks down in eternal

inflation."

The new theory is based on

string theory, one of the frameworks that attempts to reconcile general

relativity with quantum theory by replacing the point-like particles in

particle physics with tiny, vibrating one-dimensional strings. In string

theory, the holographic principle proposes that a volume of space can be

described on a lower-dimensional boundary; so the universe is like a hologram,

in which physical reality in 3D spaces can be mathematically reduced to 2D

projections on their surfaces.

The researchers developed a

variation of the holographic principle that projects the time dimension in

eternal inflation, which allowed them to describe the concept without having to

rely on general relativity.

This then allowed them to

mathematically reduce eternal inflation to a timeless state on a spatial

surface at the beginning of the Universe - a hologram of eternal inflation.

"When we trace the

evolution of our universe backwards in time, at some point we arrive at the

threshold of eternal inflation, where our familiar notion of time ceases to

have any meaning," said Hertog. In 1983, Hawking and

another researcher, physicist James Hartle, proposed what is known as the 'no

boundary theory' or the 'Hartle-Hawking state'. They proposed that, prior to

the Big Bang, there was space, but no time.

So the Universe, when it actually began, expanded from a very single point, but doesn't have a boundary. According to

the new theory, the early Universe did have a boundary, and that's allowed

Hawking and Hertog to actually derive more reliable predictions about the structure of

the Universe.

"We predict that our

universe, on the largest scales, is reasonably smooth and globally finite. So

it is not a fractal structure," Hawking said.

It's a result that doesn't

disprove multiverses, but reduces them to a much smaller range - which means

that multiverse theory may be easier to test in the future, if the work can be

replicated and confirmed by other physicists. Hertog plans to test it by

looking for gravitational waves that could have been generated by eternal

inflation.

These waves are too large to

be detected by LIGO, but future gravitational wave interferometers such as

space-based LISA, and future studies of the cosmic microwave background, may

reveal them. The team's research has been published in the Journal of High

Energy Physics, and can be read in full on arXiv. Good luck.